The Sierra Leone-born, London-based stylist on his formative years and what people get wrong about African fashion.

Stylist Ibrahim Kamara has a reputation for being hands-on. In preparation for his 2026 exhibition last year at London arts centre Somerset House, Kamara dumpster-dived in the shantytowns of Johannesburg with photographer and long-time collaborator Kristin Lee Moolman. He scavenged discarded dresses, jackets, and market bags, refashioning them into new outfits, and dressing street-cast men in tight skirts and kimono gowns. Their ears, necks, and chests were festooned with costume jewellery and junk-shop brooches. The final photographs explored what black masculinity could look like 10 years in the future. Unperturbed by African sartorial codes and Western stereotypes, 26-year-old Kamara used 2026 to reawaken a thought-provoking conversation around gender presentation and black masculinity.

The cultural osmosis that plays out in Kamara’s work is shaped by his formative years. Born in Sierra Leone, he grew up in Gambia before moving to London aged 11, where he later studied at art school Central Saint Martins. Drawing on his own diasporic experience, Kamara most recently worked as costume stylist on Sampha’s stunning short film Process, directed by Beyoncé and Kendrick Lamar collaborator Kahlil Joseph. Kamara made connections between Sampha’s life in south London and his parents’ in their hometown of Freetown, contrasting traditional Sierra Leonean ashobis and reimagined Western clothing like wedding dresses and ‘70s suits.

When we spoke via phone on one of his rare afternoons off, Kamara had just got back from a job for womenswear brand Stella McCartney in Nigeria — where he and photographer Nadine Ijewere were tasked to reinterpret the Stella McCartney SS17 Collection — and was already planning his next trip to the continent for more projects this summer. In hushed tones, Kamara talked about how the DIY generation is shaking up the fashion world, and the sartorial inspiration of “new Africa.”

What are some of the misconceptions when it comes to style and Africa?

People have an idea of what visuals look like before they have seen them, based off things they’ve seen in media. It’s quite problematic because Africa has progressed so much sartorially, and what continues to be spread in the media isn’t an accurate reflection of what is going on presently. There is so much more.

Your work envisions new expressions of black masculinity. What inspires you?

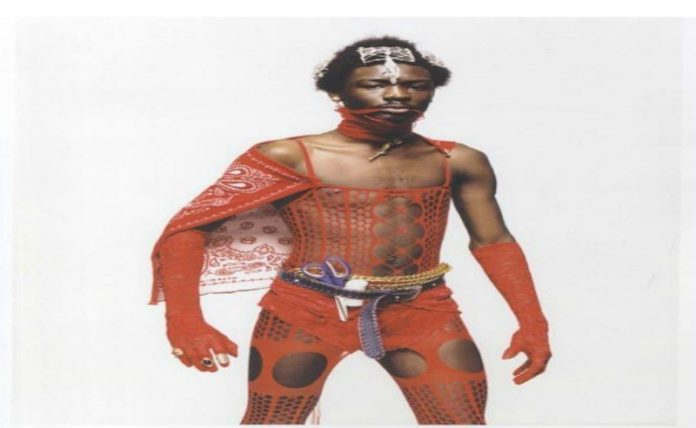

There are two boys out of South Africa called FAKA. To me, they are a perfect example of new Africa. They don’t give a fuck about what people think of them, they are reinventing what is around them. They represent the queer boys, the transgender community, the straight boys in Africa who want to try something new. Boys like FAKA are allowing men from all over the African continent, and beyond, to be themselves. You know, I live in London but I work a lot in Africa so all I can hope is that my work enlightens kids there who feel like they don’t belong, wherever they are.

I grew up in a very strict environment and 2026 was very much my coming out story, after so long of hiding who I was. 2026 is a celebration of just being yourself, and those are the things that are super important to my work. The idea that you claim your space and you fight back, at least once in your life. I want black men, gay, straight, transgender, bi, or whatever to fight back and express themselves. That’s new Africa to me.

You worked on Sampha’s Process film with Kahlil Joseph earlier this year in Sierra Leone, which is where you were born. Did that have a particular significance for you?

I felt like I was going home. In a way, it felt like I was giving back to Sierra Leone through Kahlil [Joseph] and Sampha. Being there brought back so many memories of growing up in Freetown. I visited the house I was born in. I got to work with so many beautiful young people and it just felt really refreshing to be back in that environment, creating something new and authentic.

“All I can hope is that my work enlightens kids who feel like they don’t belong.”

Do you think fashion is representing enough people, or do you think there is still some way to go?

I think there is a bit of progress. I have had support and people who I have a lot of respect for have shown admiration for my work. I think if we aren’t getting the representation needed, we can just create our own platforms though. Young people find it so hard to break through so have had to make these places to showcase what they can do. You just can now just create your own world.

Do you think the fashion industry’s current interest in diversity has the potential to bring about real change?

I really hope it is something the industry wants to talk about in the long term. If not, people like me and my friends will just have to continue to talk about it. It’s not a fad for us, it is our reality, it is where we are coming from, and we need to share our stories. There are so many black talents finally telling our stories and hopefully it just keeps going. Fashion needs to open its doors to many others like me, people who have come from nothing.

What direction do you see the fashion industry taking in the future?

I think the future is now. We are living in a DIY generation. It’s not like you have to wait around anymore to climb the ladders. We have the internet now and the DIY generation use it to showcase their work and get jobs. There’s no middle man and that’s great because you can guide yourself and learn from your own mistakes. I think the hierarchy will change, and my generation will be our own bosses.

Source: The Fader by Lynette NYLander